📚 Historical Context: How Rural Children Got to School in the 1920s-30s

Children in rural South Canterbury faced daily journeys of up to 9 kilometers through dusty summer tracks and muddy winter roads. The methods varied dramatically by family wealth:

- Walking: Most common method, 3-5 miles each way regardless of weather

- Horses: Schools maintained dedicated horse paddocks for up to 15-20 animals

- Governess carts/Gigs: Horse-drawn vehicles for more prosperous families

- Motor cars: By late 1920s, wealthy families could drive children daily

- Trains: The Fairlie Flyer connected Washdyke to Timaru for secondary students

- School buses: Introduced 1924 nationally, gradually reached South Canterbury 1936-1942

Springbrook: Harry's Walk to School and the Year That Was Taken Away

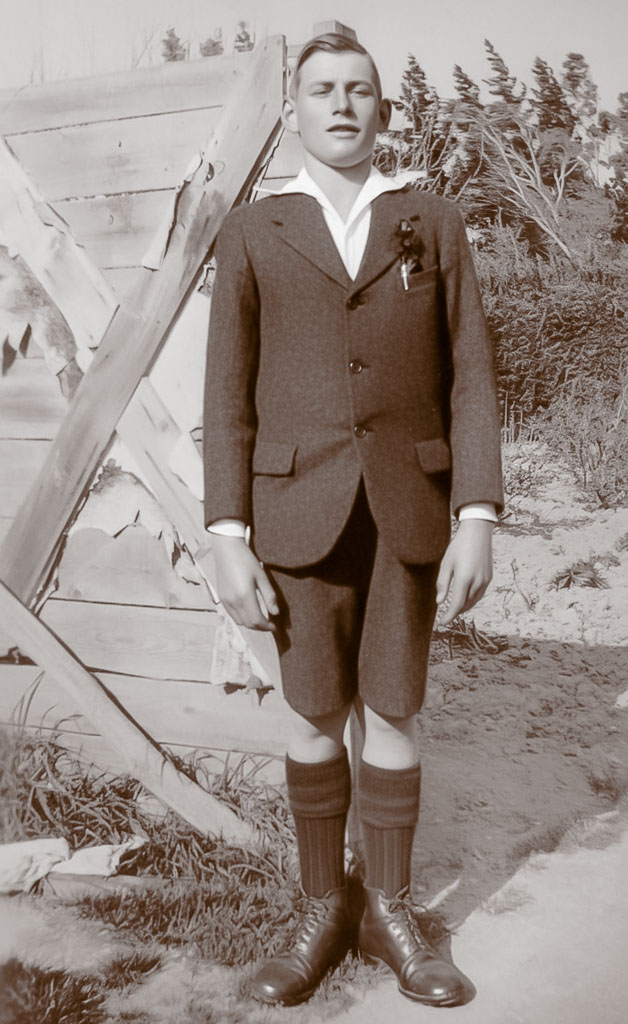

At the Cloake family's 10-acre war-allotted block at Springbrook, young Harry Cloake walked 1.7 kilometers to Springbrook Primary School each morning. He had boots - not all the children did, even in winter. His father Bertie and mother Sarah worked hard on their small holding, with Bertie and Sarah keeping bees and chooks near their cottage and Harry helping when he wasn't at school.

About Springbrook Primary School

Springbrook Primary School opened in 1895 about 2 miles south of St. Andrews township on the south bank of the Pareora River. The school building was constructed of wood and iron, containing a classroom and porch on a four-acre site. It served a small agricultural settlement with children walking distances of 1.7 kilometers or more daily.

The walk to Springbrook Primary was unremarkable to Harry. He joined other farm children on the dusty metal road in summer, the same track turned to mud each winter. Some rode horses that spent the day in the school's paddock. Some arrived by gig if their families were prosperous enough. Harry walked, sturdy boots on his feet, watching the landscape change with the seasons.

Harry was bright and he loved learning. When the time came for secondary school around 1928, Harry began attending Timaru Boys' High School. It meant traveling from Springbrook to Timaru, by a government-contracted vehicle operated by Bennett's Garage from Pareora - the Hudson Super 6, nine-seater car that ferried rural children to town.

🏫 About Timaru Boys' High School in the 1920s

Founded: 1880

Boarding facilities: Thomas House boarding hostel built in 1907, welcomed its first eight boarders in 1908

Access for rural students: Daily commuting by train (Fairlie Flyer), motor car (for wealthy families), or boarding in Timaru

Famous alumni: Olympic champion Jack Lovelock attended as a boarder from 1924 after living in Fairlie

Harry loved it. High school opened up a world beyond the farm. He excelled at athletics - 'throwing' became his passion, and he showed real promise with the javelin, discus, and shotput. The academic work came easily and for a boy from a small farm, Timaru Boys' High School represented real possibilities.

1930 Then came the Great Depression. It hit New Zealand like a hammer blow. Farms struggled. Prices collapsed. Small holdings like the Cloakes' 10-acre block felt the pressure immediately.

His daughter Marilyn would later retell: "He had just completed a year at high school and was a very bright boy, and love learning. He was absolutely gutted. But had to accept it as that was life - many children had no education in high school."

💔 The Great Depression: Hunger, Poverty, and Educational Inequality

The Great Depression reached New Zealand in 1930, creating severe and visible economic hardship that profoundly affected rural families through the 1930s.

The Visible Class Divide:

Prosperous Families:

- Owned motor cars (by late 1920s, NZ had one car per nine people)

- Could afford boarding fees for secondary school

- Children had boots and proper clothing

- Could continue education through Depression

Struggling Families:

- Children walked barefoot year-round

- Working children had no lunch on threshing mills

- Education ended after primary school

- Children kept home for farm labor

Harry went to work. Not on the family farm alone, but on the threshing mills that traveled from farm to farm during harvest season. These were hard, dusty, dangerous jobs. Harry was still a teenager but stood 6 feet tall and could lift a large sack of grain 'over the wagon wheel' as son Russell would recall. Harry was to grow exceptionally strong, to hold athletics records for decades.

On the threshing mills, he saw Depression poverty up close. Some boys his age arrived with no lunch at all. Their families simply had nothing to give them. Harry's mother Sarah always made sure he had sandwiches. Marilyn recalls Harry's stories of sharing them with the boys who had nothing. It wasn't charity - it was survival, community, the way rural people got through the worst times. Those hungry boys would remember the kindness; Harry would remember how close to the edge some families lived.

Geoffrey learned about not wasting food from Harry's experiences. At meal times, Harry was often heard to say: "When there's food, eat it. You may never know where your next meal will come from!"

The athletics he'd loved at high school? That passion never left him. He never needed to practice, working on threshing mills and the family farm was more than sufficient. He simply turned up on athletics days, winning all the way. But the sting of having his education cut short - that stayed with him too.

Washdyke/Rosewill: Doreen's Governess Cart and the Railway to Timaru

Thirteen kilometers away at Washdyke/Rosewill, Doreen Stocker's childhood followed a different trajectory. Her family's 64-acre farm represented a level of prosperity that insulated them somewhat from the worst of the Depression. Not wealthy - they worked hard for everything they had - but stable enough to weather the storm.

For primary school, Doreen attended Washdyke Primary School, just 5 kilometers from the farm. She too was bright, achieving the school's dux medal before moving onto high school. When she was old enough - she got her license at 15 - she drove the family's Rugby Durrant, which her grandfather affectionately called "Miss Durrant." Before that, she drove the governess cart, collecting other children along the way, the horse knowing the route as well as any driver.

🚂 Washdyke Primary School and the Fairlie Flyer Connection

Washdyke Primary School: Established 1874 just north of Timaru along the Fairlie railway line

Strategic Location: Washdyke was where the Fairlie Branch railway met the Main South Line, making Washdyke station the boarding point for students heading to Timaru secondary schools via the Fairlie Flyer.

The Fairlie Flyer Railway Service:

- Route: Washdyke to Fairlie (58.2 kilometers)

- Opened: Stages from 1875-1884

- Stations: Pleasant Point, Sutherlands, Kakahu, Albury, Fairlie

- Passenger service: The "Fairlie Flyer" ran until 1930

- After 1930: Mixed passenger/freight trains until 1953

The governess cart meant responsibility and independence. Doreen would harness the horse, drive to Washdyke Primary, collect younger children from neighboring farms, and deliver them all safely to school. The horse spent the day in the school's paddock, and in the afternoon, the process reversed - children piled into the cart for the journey home.

When Doreen was ready for secondary school, she attended Timaru Technical College. The Washdyke location was strategically perfect - right where the Fairlie Branch railway met the Main South Line. Doreen could drive the governess cart (and later, "Miss Durrant") to Washdyke station, catch the Fairlie Flyer train into Timaru, attend school all day, and return by train in the afternoon.

Sometimes she collected younger siblings from Washdyke Primary on the way home. Sometimes she helped pick up supplies in town. The ability to drive and the family's ownership of both a horse-drawn cart and eventually the Rugby Jurante gave Doreen options that many rural children never had.

She completed three years at Timaru Technical College - a significant achievement during the Depression years when many families pulled their children out of school entirely. The Stocker family valued education and had the means to support it, even when times were hard.

The Stone on the Fence Post: Helping Swaggers Through the Depression

The Stocker family's relative stability during the Depression showed itself in another way: they helped the swaggers - the itinerant workers who walked the roads looking for food and work.

🎒 Depression-Era Swaggers: The Men on the Road

Swaggers (also called "swagmen" or "sundowners") were itinerant workers during the Depression who traveled from farm to farm seeking work, food, and shelter. They carried their belongings in a "swag" - a rolled blanket containing their possessions.

The Swagger Code:

Swaggers developed a subtle signaling system to indicate which farms were receptive to helping:

- Stone on fence post: Indicated farm would provide food and shelter

- Chalk marks on gates: Various symbols indicated hospitality level

- Word of mouth: Swaggers shared information about helpful farms

Typical Arrangement:

- Swagger arrives at gate, checks for signal

- Approaches house, asks for work in exchange for meal

- Offered food and place to sleep (usually barn)

- Morning chores: split wood, milk cows, mend fences

- Given food for the road, moves on

Many farms turned swaggers away. Some were hostile so they placed a stone on the farm fence post - a subtle signal to those who knew the code that this farm would help. Son Geoffrey remembers his mum saying they had a policy: accept two swaggers maximum per night, feed them, and let them to do morning chores before moving on.

It was practical charity. The swaggers got a meal and a place to sleep in the barn. In the morning, they'd split wood, milk cows, mend fences - whatever needed doing - then move on with food for the road. For the Stockers, it was the right thing to do. They had enough to share, even if not much.

Doreen grew up seeing this. She saw men arrive at the gate, check for the stone, approach cautiously. She saw her parents feed hungry men who'd been walking for days. She saw the morning chores done with quiet dignity before the swaggers shouldered their swags and walked on.

It taught her something about the Depression that Harry learned on the threshing mills: some people had enough; some people had nothing. And whether you ended up with enough or nothing often had little to do with how hard you worked.

Two Paths Converging

The Contrast in Their Experiences

Harry's Journey:

- 10-acre war-allotted block

- Walked 1.7km to Springbrook Primary

- 1 year at Timaru Boys' High School

- Education ended by Depression (1930)

- Worked threshing mills as teenager

- Shared sandwiches with hungrier boys

- Dreams deferred by poverty

Doreen's Journey:

- 64-acre farm

- Drove governess cart to Washdyke Primary

- 3 years at Timaru Technical College

- Got driver's license at 15

- Took Fairlie Flyer to school

- Family helped swaggers with stone signal

- Relative privilege with responsibility

Harry Cloake and Doreen Stocker both came of age during the Depression, but their experiences diverged sharply. Harry's education ended after one year of high school - a devastating blow for a bright boy who loved learning. He worked on threshing mills, shared his sandwiches with hungrier boys, and channeled his competitive spirit into athletics.

Doreen completed three years at Timaru Technical College, drove the family's Rugby Durant, and grew up on a farm that could afford to help others even during the hardest years.

When they eventually met and married, they brought these different perspectives together. Harry knew what it was to have dreams deferred by poverty. Doreen knew the responsibility of relative privilege - the stone on the fence post, the shared meal, the morning chores.

🍯 From Depression to Innovation: Building Cloake's Honey

Together, Harry and Doreen built something remarkable that echoed the lessons of their Depression-era childhoods.

Harry's Beekeeping Journey:

- Learned basics from father Bertie at Springbrook

- Worked as policeman in Greymouth before returning to beekeeping

- Developed the Cloake Board for queen bee rearing

- Perfected creamed clover honey process

- Built one of South Island's largest apiaries with family

The Philosophy of Sharing:

Harry could have patented the Cloake Board and made money from it, but instead, he gifted it to the world - just as he did with the creamed clover honey process.

This generosity echoed both:

- The shared sandwiches on the threshing mills

- The stone on the Stocker fence post

- The Depression-era understanding that community survival mattered more than individual profit

That generosity echoed both the shared sandwiches on the threshing mills and the stone on the Stocker fence post.

Cloake's Honey, which grew to become one of the largest apiaries in the South Island with the help of family members, represented triumph over the Depression years that had cut Harry's education short and sent him to work on threshing mills as a teenager.

Postscript: The Transport Revolution

By the time Harry and Doreen's own children came along, the world had changed. School buses replaced governess carts. The Fairlie Flyer's passenger service had been cancelled in 1930 - the same year Harry's high school education ended - though freight trains continued for decades.

The horse paddocks at schools were ploughed up and converted to playing fields. Rural children no longer arrived on horseback or walked miles barefoot through winter. The small schools like Springbrook Primary consolidated into larger schools with bus services.

The School Consolidation Wave (1936-1942)

Pleasant Point area saw massive changes:

- February 1938: Pupils from Sutherlands, Kakahu, Totara Valley, Rockwood, and Hazelburn transported by bus to Pleasant Point District High School

- February 1939: Rosewill School consolidated

- 1942: Waitohi pupils transferred

The horse paddock that once accommodated fifteen to twenty gigs was ploughed up and converted to agricultural plots, symbolizing the transition from horse-based to motorized transport.

But the memories remained: Harry's devastating disappointment when his education ended. The hungry boys on the threshing mills. Doreen's governess cart journeys collecting children for school. The Fairlie Flyer steaming into Washdyke station. The stone on the fence post signaling help for swaggers.

These weren't just family stories - they were the lived reality of Depression-era South Canterbury, where the distance between prosperity and poverty could be measured in the 13 kilometers between Springbrook and Washdyke/Rosewill, or in the difference between bare feet and boots, between walking and driving, between one year of high school and three.

This story draws on family memories, historical research, and the recollections of Harry's family. Harry Cloake (b. 1915) and Doreen Stocker (b. 1918) married and built their lives together in South Canterbury, contributing significantly to New Zealand's beekeeping industry while never forgetting the lessons of their Depression-era childhoods.

Want to Learn More About Rural School Transport?

📚 Historical Deep Dive: How Rural Children Reached School in 1920s-30s South Canterbury

Harry and Doreen's school experiences were part of a larger story of rural education in South Canterbury. From horse paddocks at every country school to the Fairlie Flyer steam train, from barefoot walks in winter to governess carts collecting children along muddy tracks - the ways rural children reached school reveal much about the era's technology, inequality, and community values.

Our comprehensive article explores:

- Why schools maintained dedicated horse paddocks for 15-20 animals

- The reality of walking 3-5 miles daily regardless of weather

- How the Fairlie Flyer connected Washdyke to Timaru for secondary students

- The school bus revolution of 1936-1942 and the consolidation wave

- The stark class divisions exposed by the Great Depression

- Primary sources and research records for genealogists

Read the full article: How Rural Children Reached School in 1920s-30s South Canterbury →

📖 Further Reading & Research Sources

Primary Sources for This Story:

- Family memories and photographs

- Recollections of Harry's children, Meryn, Marilyn, Russell, Geoffrey

- South Canterbury Genealogy Society school records

- Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand - Country Schooling

- Fairlie & District Schools histories

- Pleasant Point: A Centenary of Schooling 1868-1968

Further Research:

- Papers Past: Timaru Herald 1864-1945 (digitized newspaper archive)

- South Canterbury Museum: Aoraki Heritage Collection

- Archives New Zealand Christchurch: Canterbury Education Board records from 1876