Cornish Roots: A Family Story from Cargreen to Canterbury

When Bertie Thomas Cloake stepped aboard the SS Corinthic in 1912, he carried with him more than just his belongings. He brought the skills, values, and resilience forged through generations of his family's life on the banks of Cornwall's River Tamar. This is the story of the Cloake family of Cargreen—market gardeners, bargemen, and small farmers who embodied the spirit of rural Cornwall during its most transformative era.

The Cargreen that Shaped the Cloakes

A Riverside Village at the Heart of Change

Cargreen in Bertie's childhood was a place of remarkable industry and beauty. This small hamlet in Landulph parish, perched on the western bank of the River Tamar just three miles north of Saltash, had evolved from a medieval fishing port into Cornwall's premier market gardening center. The village name itself—derived from the Cornish "Karrekreun" meaning "an outbreak of hard rock jutting into the Tamar"—spoke to the solid foundation upon which generations of Cloakes had built their lives.

The 1891 census, taken when seven-year-old Bertie was learning his letters, captured Cargreen at its peak. The village supported four shops, a post office run by the Braund family, two public houses (including the Royal Oak on the quayside, later renamed the Crooked Spaniards), and dozens of market garden operations. Every evening during the growing season, the quay bustled with activity as market gardeners brought their harvests—daffodils, strawberries, early vegetables—to be loaded onto paddle steamers bound for Devonport Market and the London trains beyond.

The Tamar Valley's Fame: The valley's unique microclimate—protected from northeast winds by rolling hills, blessed with abundant rainfall and south-facing slopes that warmed quickly—produced the "earliest" crops in Britain. The famous Tamar Double White Daffodil could fetch premium prices at Covent Garden, arriving within 24 hours of picking thanks to the railway revolution.

The Cloake's as neighbours

Bertie was the son of David Thomas Cloake (1859–1940) and his first wife, Amanda Mary Hocking (1859–1895). They were deeply embedded in this community. When the 1891 census enumerator walked through Cargreen, he recorded three Cloake households within close proximity on the main street:

1891 Census listings

- Number 16: John Cloake (72, farm labourer) and Mary Ann Cloake (70), Bertie's grandparents

- Number 26: David Thomas Cloake (32, market gardener), Amanda Mary (31), Bertie (7, scholar), Irene (5), and Jane Gill (14, Amanda's half-sister)

- Number 25: Frederick Cloake (29, agricultural labourer), Mary, and their young children

This clustering wasn't unusual—it was how rural Cornwall worked. Families and even in-laws, lived side by side, sharing labour during harvest, pooling resources, and supporting each other through hardship. The house names today are—Powesva for David's first home and Primrose Cottage for Frederick's—spoke to a time when every cottage had its own identity.

David Thomas and Amanda (nee Hocking) Cloake: Bertie's Parents

From Bargeman to Market Gardener

Bertie's father David was a man who embodied the adaptability Cornwall demanded of its people. Born in January 1859 in Landulph, David's working life traced Cornwall's economic evolution.

In his youth, David worked as a bargeman, poling flat-bottomed lighters laden with lime, timber, and agricultural goods along the tidal Tamar. A Masonic Lodge record confirms that on 6 February 1882, at age 23, David joined what was likely St. Aubyn Lodge No. 859 in Saltash, listing his occupation as "bargeman." This wasn't merely transport work—it was skilled navigation of treacherous waters, reading tides and weather, knowing every shoal and current in the river. Bargemen earned 15-20 shillings weekly, enough for a young man to save toward marriage and independence.

Marriage and Transformation: David married Amanda Mary Hocking in 1882, bringing together two established Cornwall families. By 1891, he had transformed himself into a market gardener—a significant step up from agricultural labourer. The census shows him as neither employer nor employee, suggesting he worked his own small holding, likely renting even owning land behind their home.

Tragedy and Resilience: Two Marriages, Two Families

David and Amanda bore five children, four surviving, first at nearby Penyoke, then Cargreen in Landulph Parish:

Amanda's Children (1883-1895)

David and Amanda had five children, with four surviving, during their thirteen years of marriage, first at nearby Penyoke, then Cargreen.:

- Bertie Thomas Cloake (1883-1960) - who emigrated to New Zealand

- Irene Mary Cloake (1886) - Bertie's closest sibling in age

- Ida Pamela Cloake (1891-1957) - born the same year as Iris Freda

- Iris Freda Cloake (c. 1893-1894) - died young, likely before her fourth birthday

- Arthur Bernard Cloake (15 August 1895-1971) - born just three months before his mother's death

Selina's Children (1898-1911)

After Amanda's death in December 1895 and David's remarriage to Selina Waters Hocking in 1897 (Amanda's other half-sister), Jane remained with the family. This continuity was crucial—she was the one constant for the five children who had lost their mother, providing familiar care while their father remarried and their household transformed. For Jane, staying with David meant continuing the only secure home she had known as an adult.

After David's remarriage to Selina, seven more children were born:

- David Thomas Cloake (December 1898, died March 1899) - infant mortality, lived only 3 months

- Frederick David Cloake (June 1900) - named perhaps for David's brother Frederick

- Minnie Cloake (1901) - later married Owen Pett in 1931

- David Cloake (September 1903) - the surviving David who became a farmer and inherited Warren House

- Hedley Cloake (c. 1907) - helped work Warren House, died 1967 in Calstock

- Philip Cloake (1909, died in infancy) - another heartbreaking infant loss

- Harry Bennett Cloake (c. 1911) - the youngest child, whose middle name "Bennett" may reference cousins.

A Blended Family Across Generations: This created a blended family with a significant age gap: when Harry was born in 1911, his half-brother Bertie was 27 years old—old enough to be Harry's father. The family experienced the painful reality of Victorian infant mortality—three children lost out of twelve born. Yet nine survived to adulthood, an impressive number reflecting both the family's relative prosperity and Selina's resilience through so many pregnancies.

Jane Gill's Role in the Family

Also in the household was Jane Gill (born 1877 in Pillaton), Amanda's half-sister through their mother Mary Ann Rowe's earlier relationship. The 1891 census shows 14-year-old Jane living with David and Amanda at Address 26 in Cargreen, listed as "sister-in-law," helping with childcare, household tasks, and learning market gardening skills. But Jane's presence wasn't simply family helpfulness—it was mutual necessity. Jane had survived polio, which left her with physical disabilities that would have made marriage and independent living extremely difficult in Victorian Cornwall.

Polio often left survivors with paralyzed or weakened limbs, making the physical demands of farm work, housekeeping, or bearing children nearly impossible. For Jane, living with her half-sister's family provided security, purpose, and protection in a world with no disability benefits.

After Amanda's death in 1895, Jane remained with David, providing crucial continuity for the four children who had lost their mother. When David remarried Amanda's other half-sister Selina in 1897, Jane's role evolved from teenage helper to household manager to support Selina with yet another 5. By 1901-1911 at Bag Mill, she was formally listed as "housekeeper and assistant," for the domestic side of a substantial farming operation—supervising meal preparation, organizing household supplies, and training the older girls in domestic skills.

For a woman with polio in rural Cornwall, this position represented both security and dignity: meaningful work that contributed to family prosperity while being protected from the poverty that would have awaited a disabled woman living alone.

Family notes indicate "Jane Housekept for David and Selina Cloake until Jane died"—she remained with them for life, a testament to the mutual loyalty that characterized rural Cornwall's best qualities.

The Moves to Bag Mill and Warren House

A Strategic Move to Medieval Mill Country

By 1901, the expanding family—now including twelve people spanning three generations—had moved to Bag Mill in the parish of St. Stephens-by-Saltash. This represented significant economic advancement and a return to David's bargeman roots through the property's waterway connections.

Location and Water Access

Bag Mill lay about 2 miles west of Saltash town center, crucially positioned along the Lynher River tributary. The Lynher flows south from Bodmin Moor before joining the Tamar estuary near Saltash. This location gave the Cloake family:

- Market access via the Tamar: David could still reach Plymouth markets by water using his bargeman skills

- Seclusion for livestock farming: Room for dairy cows and poultry away from Cargreen's quay bustle

- Natural irrigation from the leat: The medieval water channel that once powered the mill now watered fields—essential for clovers and brassicas

The property's medieval origins as a water mill (referenced in 1200s records as part of Trematon Manor) meant it had been designed around water management. For a former bargeman like David who understood river systems, Bag Mill was a natural fit.

The 1901 Household at Bag Mill

The census captures a complex household managing both family and farm:

- David Thomas Cloake (42) - elevated from "market gardener" to "farmer"

- Selina Waters Cloake (31) - managing household and children ranging from infant to teenager

- Jane Gill (24, born 1877 Pillaton) - now formally listed as "housekeeper" rather than sister-in-law

- Bertie Thomas Cloake (17) - "assisting on farm," transitioning from school to full farmwork

- Irene Mary Cloake (15) - helping with household management and younger children, likely working alongside Jane

- Ida Pamela Cloake (10) - old enough for light farm chores

- Arthur Bernard Cloake (6) - still in school years but learning farm life

- Frederick David Cloake (infant, born June 1900) - first child born at Bag Mill

The family occupied a 5-room cottage, with holdings estimated at 30-40 acres. This was real mixed farming: dairy cows producing milk for Plymouth markets via Saltash, eggs and poultry sold locally, vegetables and fruit for market and family. The waterway connections meant David could transport milk churns and produce by boat during peak seasons.

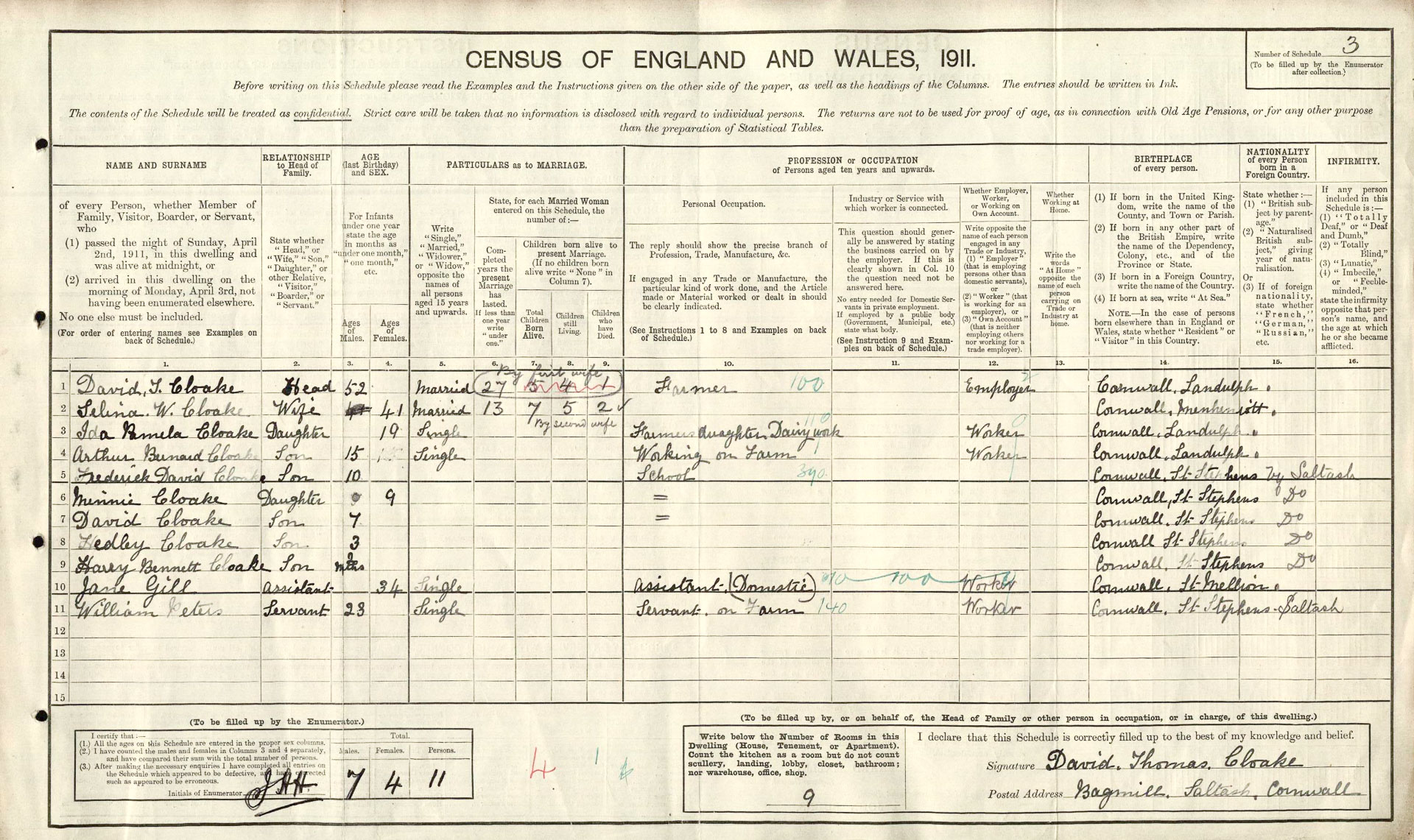

The 1911 Census: Peak Prosperity and Continued Care

A decade later, the household had expanded to 9 rooms, accommodating:

- David Thomas Cloake (52) - firmly established as "Farmer"

- Selina Waters Cloake (41) - noting "7 live births of 9 total," a sobering reference to infants lost

- Jane Gill (34) - still serving as housekeeper after two decades with the family

- Ida Pamela Cloake (19) - doing dairy work

- Arthur Bernard Cloake (15) - "assisting on farm," transitioning from school to full farmwork

- Frederick David Cloake (10) - scholar at school

- Minnie Cloake (9) - scholarl helping in house and with poultry, likely learning from Jane

- David Cloake (7) - scholarl learning farm work from father and brothers

- Hedley Cloake (3) - too young for work but absorbing farm life

- Harry Bennett Cloake (3 months old) - the baby, born around 1910-1911

- William Peters - farm labourer employed by David, indicating substantial operations

Why Bag Mill Mattered

The decade at Bag Mill (roughly 1901-1915 represented the Cloake family at their most prosperous before the Great War. The property combined waterway access, medieval water infrastructure, market proximity, and sufficient acreage (30-50 acres) for commercial mixed farming.

The Lynher River tributary meant the property had been part of the broader Tamar Valley trading network for centuries. Local farmers used the river to transport lime, coal, manure, and produce—continuing the ancient patterns David had known as a young bargeman.

By 1915-1920, David would move to Warren House in Tideford, seeking even more land (90 acres). But Bag Mill remained the crucible where the Cloake children learned commercial farming, where Bertie developed the livestock skills he'd adapt to beekeeping in New Zealand, and where David proved he could manage a substantial mixed farm successfully—all while Jane Gill, despite the limitations polio imposed, quietly maintained the household that made it all possible.

A Reminder of Rural Resilience: Her story reminds us that Victorian farming families survived not just through the labor of the able-bodied, but through finding roles where everyone—regardless of physical limitations—could contribute their skills and receive care in return.

Bertie's Childhood: Growing Up in Cargreen's Golden Age

A Scholar in a Market Garden World

When the 1891 census recorded seven-year-old "Berti" Cloake as a "scholar" living at Cargreen, it captured a boy at the threshold between childhood and the working life that would define him. Unlike his grandfather John, who had labored from youth without education, Bertie had the privilege of schooling—likely at the local school near Landulph Cross.

But education in rural Cornwall was never divorced from the land. After school and on weekends, young Bertie would have helped in his father's market gardens. By his teenage years, Bertie had taken on substantial responsibilities. The 1901 census at Bag Mill shows him at 17 as "assisting on farm." By 1911, at 27, he's explicitly listed as "cow/poultry man"—skilled work managing livestock that would inform his later beekeeping career.

A Village of Faces and Connections

Growing up in Cargreen meant knowing everyone. The village population numbered just a few hundred souls. Bertie would have known:

- The Braund families who ran the merchant shop with the post office and bakery where Seline grew up.

- The Rowe family next door, running a competing grocery and garden operation

- The Barrett family at the substantial Chenowyth farm

- The Gill family, cousins a few doors up—carpenters and grocers

Every family knew every other family's business, tragedies, and triumphs. This was Cornwall's strength and sometimes its constraint—the tight-knit community that sustained you but also knew your every move.

Religion and Recreation in a Methodist Stronghold

The Landulph Methodist Church, built in 1874, would have been central to Bertie's upbringing. By 1851, over 60% of Cornwall's churchgoers were Methodists—the highest proportion anywhere in the British Isles except north Wales. The chapel wasn't just for Sunday worship. It hosted:

- Sunday schools where working-class children learned reading and arithmetic

- Male voice choirs that became Cornwall's signature cultural expression

- Band of Hope temperance meetings where children pledged abstinence

- Tea treats with processions led by brass bands

- Missionary meetings with lantern lectures

- Class meetings for spiritual development

Methodist values—hard work, temperance, self-improvement, mutual aid—shaped Bertie's character as much as the market gardens shaped his skills.

The Shadow of Emigration

But even in Cargreen's apparent prosperity, the shadow of emigration loomed. Between 1861 and 1901, approximately 250,000 Cornish people emigrated—in each decade, about a fifth of Cornish males left, three times the average for England and Wales.

Bertie would have watched neighbors and relatives leave for America, Australia, South Africa, Canada. Letters arrived describing opportunities impossible in Cornwall. By his twenties, Bertie faced limited prospects. His father had achieved relative success, but with so many children, the farm couldn't support them all. The sea route to New Zealand must have beckoned with promise.

Cousin John Bennett (on the Rowe side) was long established in South Canterbury and would most certainly have been Bertie's reason to at least select Timaru, if not provide entree. John's brother Henry visited in 1878 and returned after witnesing John's marriage to Jane Marshall of Temuka.

The Connected Families: Hocking, Gill, Braund, Barrett

The Web of Kinship

Understanding Bertie's Cornwall means understanding the web of families intermarried across generations. These weren't distant connections—they were the people next door, the relatives at Sunday chapel, the employers and employees bound by proximity and need.

The Hocking and Gill Families: A Tangled Legacy

The Hocking family connection shaped Bertie's entire existence through an unusually complex arrangement. His father David Thomas Cloake married twice—both times to daughters of Mary Rowe of Menheniot, though by different fathers.

David's first wife, Amanda Mary (Minnie) Hocking (born 1859), was the daughter of Mary Rowe and William Hocking. She married David in December 1882 and bore him five children (four surviving), including Bertie Thomas Cloake (born December 1883). Amanda died on 13 December 1895, leaving David a widower with young children.

His second wife, Selina Waters Hocking (born 1869), was Amanda's younger half-sister through their shared mother Mary Rowe. Selina bore the middle name "Waters" because her father had died before her birth—no father appears on her birth certificate. She gave David seven more children (five surviving) between 1898 and 1911, including Harry Bennett Cloake, before her death in July 1922.

This meant Bertie's half-siblings through Salina were also his first cousins once removed—the kind of intricate family webs rural Cornwall specialized in. It was not uncommon in Victorian times for a widower to marry his late wife's sister, maintaining family connections and providing continuity for the household.

Mary Rowe herself had lived an extraordinary life by Victorian standards—four known marriages or partnerships: first to William Hocking (Amanda's father), then to the father of Selina (surname possibly Waters, William Hocking had died before Selina's birth), then to carpenter Philip Gill in 1872, and finally to William Braund in 1880.

The Hocking family had roots in Menheniot and Quethiock, working as farmers and market gardeners. The connection brought respectability—the Hockings were a step above pure agricultural laborers, owning or renting their own holdings.

The Bennett and Rowe Families: Ancestral Connections

The Bennett name carried special significance in the Cloake family—so much so that Bertie's half-brother was named Harry Bennett Cloake, likley in honor of Jane Bennett, David Thomas Cloake's great-great-grandmother. Jane Bennett (born 1780) married William Cloak first, giving birth to John Cloak in 1818. , then married Richard Copplestone as her second husband in 1832.

The Bennett and Rowe families were closely intertwined. William Bennett (Jane Bennett's brother) married Anne Snell first, then Jane Rowe—Mary Rowe's older sister—in 1848. The Rowe sisters, daughters of Richard Rowe and Mary Skinner of Menheniot, married into different branches of this Cornish network: Jane into the Bennetts, Mary into the Hockings and later the Gills and Braunds. These connections created a remarkable genealogical web spanning Menheniot, Quethiock, St Germans, and the riverside communities along the Tamar.

The Bennett family holdings in Quethiock included Ludcott Farm and Trehenest, establishing them as substantial landholders in the parish alongside their connections through marriage to the Cloake, Rowe, and other prominent Cornish families.

The Gill Family: Carpenters and Kin

When 14-year-old Jane Gill lived with David and Amanda in 1891, she represented another crucial family connection. Jane was Amanda's half-sister through their mother Mary Rowe's third marriage to Philip Gill in 1872, making her Bertie's aunt despite being only seven years older.

The Gill family were skilled tradesmen—carpenters represented a skilled artisan class above agricultural laborers. They built the packing sheds where flowers were sorted, constructed boats, maintained quay infrastructure, and built homes. This connection to the trades added another dimension to Bertie's family network beyond farming and market gardening.

The Braund Family: Merchants and Boatmen

The Braund family was arguably Cargreen's most prominent dynasty during Bertie's childhood, and they carried a direct family connection through Mary Rowe's fourth marriage to William Braund in 1880. John Braund ran a commercial empire from Address 10:

- His daughter Maud M. Braund worked as postmistress

- Multiple Braund relatives worked as bakers

- The operation combined merchant trade, baking, and postal services

Richard Braund operated as "Boatman, Employer," managing river transport. His boats ferried flowers and produce to Devonport market—essential logistics for the entire market gardening industry.

The Braund presence was so extensive that they continue farming in Cargreen today—Michael and Martin Braund currently operate Penyoke Farm growing lettuces, maintaining a relationship spanning 15+ years.

The Barrett Family: The Farming Elite

The Barrett family dominated Cargreen's agricultural landscape and connected to the Cloakes through John Cloak's marriage to Mary Ann Barrett in 1845—making them Bertie Cloake's paternal grandparents.

The Barrett family stretched back to 1788 in the Pillaton and St Mellion areas. Multiple Barrett branches pursued different agricultural specializations—the main Chenowyth farm, market gardens, and various laboring roles. They represented what successful farming looked like: multigenerational landholding, employment of others, economic security.

Why Bertie Left: Cornwall's Economic Crisis

The Great Emigration and Its Causes

Bertie's 1912 emigration wasn't unusual—it was typical. Understanding why requires grasping the catastrophe that befell Cornwall between 1860 and 1900.

The Mining Collapse

In 1866, copper prices plummeted following the collapse of bankers Overend and Gurney, causing famous old copper mines to close. New abundant mineral reserves in the United States, Australia, and South America meant Cornwall's ancient industry became economically unviable. By 1870, tin prices also collapsed.

"They come to me for advice. If they have a few pounds out of the wreck my advice always is 'Emigrate!' And accordingly nearly a hundred in the current year go across the seas." — RS Hawker, 1862

Agricultural Distress

Agricultural distress compounded the crisis:

- Potato blight caused harvest failures

- Cheap foreign wheat lowered prices and wages

- Enclosure acts reduced access to common land

- Limited opportunities even for skilled workers like market gardeners

The Pull of New Zealand

While Cornwall pushed people out, New Zealand pulled them in. The Vogel Immigration Scheme (1871-1888) had specifically targeted Cornish people, recruiters told to focus on "Cornish and Scots who were known for their hard work ethic and therefore deemed particularly ideal for colonial life."

Though the main assisted passage scheme had ended by 1912, the networks persisted. Chain migration—where early emigrants encouraged family and friends to follow—was powerful in Cornish communities. Bertie's brother Arthur also emigrated to New Zealand, as did Sarah's sisters Annie and Emmy.

The attractions were tangible:

- Land ownership: In New Zealand, a capable farmer could own substantial acreage impossible in Cornwall

- Economic opportunity: No mining collapse, no agricultural depression

- Family networks: Relatives who'd gone before provided guidance and support

- Climate: Canterbury's temperate conditions suited Cornish agricultural skills

For Bertie at 27-28, a cow and poultry man with market gardening experience, the calculation was stark: stay in Cornwall with limited prospects, or risk everything for New Zealand's promise. He chose the risk.

The Journey: From Cargreen to Canterbury

Marriage and Departure

In 1911, Bertie married Sarah Couling (1884-1948) in Devonport, Devon. Sarah, born in Treverbyn, St. Neot (Cornwall), came from Polbathic. Family lore remembers her as a "sleepwalking moorland lass." Their first child, Mary, was born in 1912 in Newton Abbot.

Bertie departed first, establishing a foothold in South Canterbury. Then in September 1913, Sarah and baby Mary followed aboard the SS Corinthic, a White Star Line vessel built in 1902.

Six Weeks of Seasickness

The voyage was miserable for Sarah. The Corinthic, accommodating 688 passengers in three classes, departed Southampton and stopped at Plymouth before the approximately six-week journey to Wellington.

Sarah was seasick for the entire six weeks. Sharing a cabin with six other women, she couldn't care for baby Mary. Strangers took turns nursing the infant, feeding her, walking her when she cried—a testament to the shipboard community that formed among emigrants.

Imagine Sarah's state upon arrival: exhausted from six weeks of nausea, worried about her daughter, uncertain about her new home, separated from everything familiar. Yet she persevered, reuniting with Bertie and beginning their New Zealand life.

Settlement at Springbrook

The family settled at Springbrook near Fairview in the Timaru area. South Canterbury's rolling plains, backed by distant mountains, must have reminded Bertie of Cornwall's valleys—but on a vastly different scale. Here was land in abundance, clover fields stretching to the horizon, opportunities limited only by willingness to work.

Bertie initially worked as a farmer, applying his Cornish agricultural knowledge to New Zealand's conditions. But his transformation into a pioneering beekeeper—starting with "just a wee hive" and eventually creating one of the South Island's largest apiaries—brought from Cornwall:

- Work ethic: Methodist emphasis on industry and self-improvement

- Agricultural knowledge: Crop timing, livestock management, understanding of microclimates

- Adaptability: The Cloake family had shifted from bargemanship to market gardening to mixed farming

- Community values: Chapel culture of mutual aid, sharing innovations, supporting neighbors

- Family orientation: Large families working together, multiple generations cooperating

These weren't abstract values—they were practical survival skills that served Bertie as well in Canterbury as they'd served his father in Cornwall.

The 1928 Return Visit: A Son and Father Reunited

Across Oceans to Home

In 1929, the passenger ship Rotorua docked at Southampton carrying two travelers: Bertie Thomas Cloake (age 44-45) and his father David Thomas Cloake (age 70). They had sailed from New Zealand together, with David visiting his son's adopted homeland and Bertie escorting his father home.

This journey—16 years after Bertie's emigration—must have been profoundly emotional. David saw firsthand what his son had built: the beekeeping operation, the New Zealand grandchildren, the prosperity possible in a young colony. For Bertie, showing his father around South Canterbury was both pride and perhaps sadness—here was everything he'd achieved by leaving Cornwall.

The return voyage gave them weeks together, talking about family left behind, changes in Cargreen, the market gardening industry's evolution. When they docked at Southampton and David continued to Warren House while Bertie returned to New Zealand, both men knew they might not meet again. David was 70, the journey exhausting, the distance immense.

Whether Bertie made another visit in 1953 (possibly for his father's memorial or to visit other relatives) isn't fully documented, but the 1928 journey stands as a bridge between two worlds—the Cornwall of memory and the New Zealand of reality.

Legacy Across Two Hemispheres

Cornwall: The Cloake Name Endures

In Cargreen today, Cloake Place (postcode PL12 6NX)—a modern amenity housing development—bears the family name. This honor, typically reserved for families of long-standing community significance, testifies to the Cloakes' impact.

David Thomas Cloake lies buried at St. Germans Priory, where his ancestors worshipped for generations. The Landulph Methodist Church where Bertie was raised still stands, serving a smaller congregation but maintaining traditions of community service.

Warren House endures as a private residence and farm, occasionally appearing in property listings at £500,000-600,000. The Braund family still farms at Penyoke. The Royal Oak pub (later Crooked Spaniards) closed in 2007, ending centuries of continuous operation.

The Industry's End: The market gardening industry that shaped Bertie's childhood collapsed in the 1960s when the Beeching railway cuts ended the freight services the trade absolutely required. Once daffodils couldn't reach London within 24 hours, the industry died. Today, Cargreen is a quiet residential village.

New Zealand: Innovation and Industry

In South Canterbury, Bertie's legacy flourished through multiple generations:

- Cloakes Honey Limited, formally incorporated December 12, 1963

- The Cloake Board, invented by sons Harry and Mervyn for efficient queen bee rearing, now used worldwide

- The creamed honey process, developed independently and shared freely rather than patented

- Award-winning honey: First prize for White Liquid Honey at National Beekeepers' Association conference (1933)

A Legacy of Generosity: When an American traveled to New Zealand to sell patent rights for creamed honey, he discovered the Cloakes had already figured it out—and had chosen NOT to patent it, sharing it freely to strengthen the broader industry. This generosity, echoing Methodist emphasis on community benefit and Cornish cultural traditions of mutual aid, marked the family as builders rather than monopolists.

The Family Continues

Bertie and Sarah raised a large family:

- Mary (born England, emigrated as infant)

- Harry (married Doreen Helen Stocker, November 2, 1940)

- Myra (became Mrs. Rouse)

- Mervyn (continued family business, co-invented Cloake Board)

- Russell, Margaret, and Janet (all involved in family business)

Their grave in Timaru cemetery is still visited by descendants who "continue to celebrate their Cornish roots to this day," maintaining connections through family history, genealogical research, and cultural practices.

Conclusion: The River and the Plain

Carrying Cornwall Forward

When Bertie Thomas Cloake stood on Cargreen's quay as a boy, watching paddle steamers load daffodils for London, he couldn't have imagined his future. The River Tamar that defined his childhood—its tides and mists, its salmon and trade, its connection to Devon and the wider world—would give way to Canterbury's plains, where bees pollinated clover and honey flowed like the river of his youth.

But he carried Cornwall with him: the Methodist faith that emphasized hard work and mutual aid, the agricultural knowledge passed from grandfather to father to son, the adaptability that let Cloakes shift from bargemanship to market gardening to mixed farming, the community values that made him share innovations rather than hoard them.

David Thomas Cloake's life (1859-1940) bridged Cornwall's transformation from mining prosperity to agricultural reinvention. He was bargeman on the Tamar, market gardener in Cargreen's golden age, farmer weathering economic collapse and world wars. His Masonic ring and Methodist faith, his two marriages and twelve children, his journey to New Zealand at 69—all testify to resilience across eight decades.

Bertie's emigration (1912-1913) and pioneering beekeeping (1923-1960) carried that resilience to new lands. The boy who learned to time daffodil harvests in Cornwall's microclimate became the man who built South Canterbury's largest apiary. The child of Landulph Methodist Church became the innovator who shared creamed honey techniques freely.

The Cloake family story—from Pillaton's agricultural laborers to Cargreen's market gardeners to New Zealand's beekeeping pioneers—embodies the Cornish diaspora's broader narrative: economic necessity driving exodus, but also ambition, skill, and values that traveled oceans and built new communities while never quite forgetting the river's edge where it all began.

For the Cloake descendants in New Zealand, may this account help you see the Cornwall that shaped your ancestors—its villages and values, its hardships and hopes, its tight-knit communities and sweeping transformations. You carry in your veins the resilience of bargemen and market gardeners, the faith of Methodist chapels, the generosity that shares innovations freely, and the adaptability that turns strangers into neighbors across hemispheres.

Sources: This account draws on extensive research including UK census records (1841-1911), parish registers from Landulph and Pillaton, Masonic lodge records, Methodist chapel histories, emigration records, and local histories of Cargreen and the Tamar Valley. Specific citations available upon request.